So you’ve got a killer recipe for double fudge peanut butter cookies you promised your grandmother never to reveal to anyone. When you put them out at parties they disappear quicker than the Cleveland Browns chances of making the playoffs. Your friends and family have told you countless times that you could make a killing selling these cookies, but you never took them seriously. But, while recently watching your favorite showing on the Cooking Channel, you finally realize you can do what these cooks are doing and decide to launch your own cookie business. But you’ve never started a business before, let alone a food business, so where do you begin?

Since you are working with a limited budget, you rule out starting your own manufacturing facility or hiring a contract manufacturer produce the cookies for you. You narrow your options down to renting space in a shared commercial kitchen or baking out of your home. Although your friends and family rave about the cookies you give away (which they should!), you’re uncertain whether people are willing to pay for your delicious product. Based on this analysis, you decide baking in your own kitchen is the most cost effective way to go until you prove there is a market for your cookies.

Now that you’ve decided to start a home-based food business (commonly referred to as a Cottage Food business), you ask yourself: “what do I do now?” The laws and regulations governing food businesses are difficult to navigate and can seem a bit daunting, but don’t let that discourage you. In this article we will walk you through the steps to start a home-based food business under the Michigan Cottage Food Law.

Where You Can Sell

In Michigan, cottage foods may only be sold by the producer directly to the consumer at farmers’ markets, farm stands, roadside stands and similar venues. Cottage foods cannot be sold to a retailer for resale or to a restaurant for use or sale in the restaurant. Cottage foods cannot not be sold over the Internet, by mail order, or to wholesalers, brokers or other food distributors for resale. Cottage Food businesses may take orders over the phone as long as the cash transaction and delivery of the product is face to face; however, Internet orders are prohibited. Shipping or third-party delivery of cottage food products is also prohibited.

Permitted Foods

Under the Cottage Food Law, only non-potentially hazardous foods that do not require time and/or temperature controls for safety are permitted to be made in a home-based kitchen. “Potentially hazardous food” is food that can be safely kept at room temperature and do not require refrigeration. Examples of permitted foods include: Breads; Similar baked goods; Vinegar and flavored vinegars; Cakes, including celebration cakes (birthday, anniversary, wedding); Sweet breads and muffins that contain fruits or vegetables (e.g., pumpkin or zucchini bread); Cooked fruit pies, including pie crusts made with butter, lard or shortening; Fruit jams and jellies in glass jars that can be stored at room temperature (except vegetable jams/jellies); Cookies; Dry herbs and dry herb mixtures; Dry baking mixes; Dry dip mixes; Dry soup mixes; Dehydrated vegetables or fruits; Popcorn; Cotton Candy; Non-potentially hazardous dry bulk mixes sold wholesale can be repackaged into a Cottage Food product (similar items already packaged and labeled for retail sale cannot be repackaged and/or relabeled); Chocolate covered pretzels, marshmallows, graham crackers, Rice Krispies treats, strawberries, pineapple or bananas; Coated or uncoated nuts; Dried pasta made with eggs; Roasted coffee beans or ground roasted coffee; Vanilla extract (Note: these products require licensing by the Michigan Liquor Control Commission); Baked goods that contain alcohol, like rum cake or bourbon balls (Note: these products require licensing by the Michigan Liquor Control Commission).

Prohibited Foods

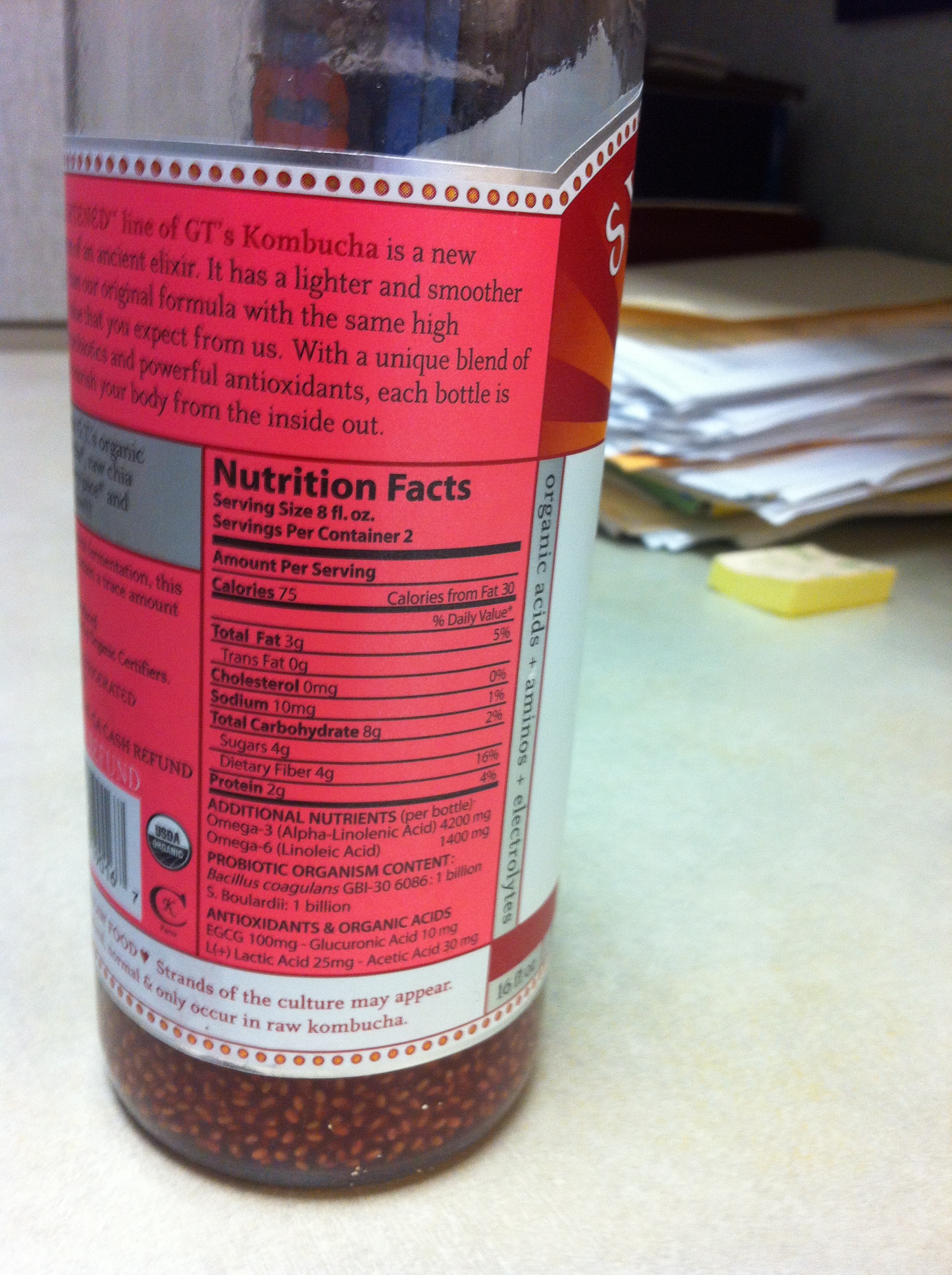

Potentially hazardous foods are not permitted to be made in a home-based kitchen. Examples of prohibited foods include: Meat and meat products like fresh and dried meats (jerky); Fish and fish products like smoked fish; Raw seed sprouts; Vegetable jams/jellies (e.g., hot pepper jelly); Canned fruits or vegetables like salsa or canned peaches; Canned fruit or vegetable butters like pumpkin or apple butter; Canned pickled products like corn relish, pickles or sauerkraut; Pies or cakes that require refrigeration to assure safety like banana cream, pumpkin, lemon meringue or custard pies, cheesecake, and cakes with glaze or frosting that requires refrigeration (e.g., cream cheese frosting); Milk and dairy products like cheese or yogurt; Cut melons; Caramel apples; Hummus; Garlic in oil mixtures; All beverages, including fruit/vegetable juices, Kombucha tea, and apple cider; Ice and ice products; Cut tomatoes or chopped/shredded leafy greens; Confections that contain alcohol, like truffles or liqueur-filled chocolates; Focaccia style breads with fresh vegetables and/or cheeses; Food products made from fresh cut tomatoes, cut melons or cut leafy greens; Food products made with cooked vegetable products that are not canned; Sauces and condiments, including barbeque sauce, hot sauce, ketchup, or mustard; Salad dressings; and Pet food or treats.

Limitations

Currently, Cottage Food businesses are limited to $20,000 per year in gross sales. The limit will increase again December 31, 2017 to $25,000 per year. You need to maintain sales records and provide them upon request to a food inspector.

Licenses and Permits

Under Michigan law, if you qualify to operate as a Cottage Food business, you are exempt from obtaining a food establishment license. There are no application forms to complete, no registration process and you do not need to obtain a food license or permit. However, the Cottage Food Law does not exempt you from the requirements of the Michigan Food Code, such as not distributing adulterated (unsafe) food.

Local Zoning

Home-based food businesses should be aware of local laws and ordinances, including zoning and small business permitting. It is important to check with your local health inspector to determine whether your home is properly zoned for a home-based food business.

Labeling

If your product is only sold within the state in which you operate, then you are exempt from federal labeling requirements. However, your label must comply with the labeling requirements under the Cottage Food Law.

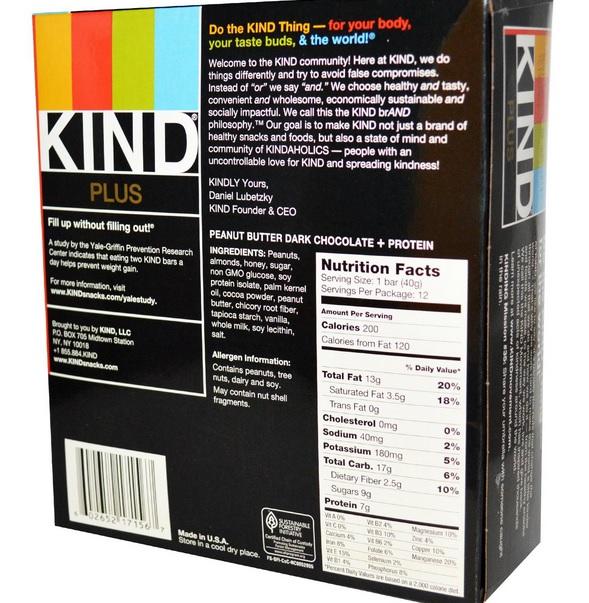

In Michigan, your product label must contain the following:

- Name and physical address of the Cottage Food operation (P.O. Box addresses are not allowed)

- Name of the Cottage Food product (all capital letters or upper/lower case)

- Ingredients in descending order of predominance by weight. If you use a prepared item in your recipe, you must list the sub ingredients as well (For example: soy sauce is not acceptable; soy sauce (wheat, soybeans, salt) would be acceptable).

- Net weight or net volume (must also include the metric equivalent)

- Allergen labeling (as specified in federal labeling requirements)

- Must include the following statement: “Made in a home kitchen that has not been inspected by the Michigan Department of Agriculture & Rural Development” in at least the equivalent of 11-point font (about 1/8″ tall) and in a color that provides a clear contrast to the background (all capital letters or upper/lower case)

Hand-printed labels are acceptable if they are clearly legible, written with durable, permanent ink and printed large enough to equal the font size requirements listed above.

Below is an example of an approved label:

MADE IN A HOME KITCHEN THAT HAS NOT BEEN INSPECTED BY THE MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE & RURAL DEVELOPMENT

Chocolate Chip Cookies

Joe’s Cookie Company

123 Chocolate Lane

Dessert City, MI 48009

Ingredients: Enriched flour (Wheat flour, niacin, reduced iron, thiamine, mononitrate, riboflavin and folic acid), butter (milk, salt), chocolate chips (sugar, chocolate liquor, cocoa butter, butterfat (milk), Soy lecithin as an emulsifier), walnuts, sugar, eggs, salt, artificial vanilla extract, baking soda

Contains: wheat, eggs, milk, soy, walnuts

Net Wt. 3 oz (85.05g)

If you have questions about starting a cottage-food business, please contact one of our attorneys at Morsel Law.

Earlier this year, Hampton Creek Inc., the maker of Just Mayo, was sued by Unilever, the maker of Hellman’s mayonnaise, and accused of false advertising for calling its egg-less spread “mayo”. Even though experts thought the claims were strong, the case was eventually dropped due to the negative publicity Unilever received which painted it as a corporate bully. As mentioned in an earlier

Earlier this year, Hampton Creek Inc., the maker of Just Mayo, was sued by Unilever, the maker of Hellman’s mayonnaise, and accused of false advertising for calling its egg-less spread “mayo”. Even though experts thought the claims were strong, the case was eventually dropped due to the negative publicity Unilever received which painted it as a corporate bully. As mentioned in an earlier