Last week President Obama signed the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard into federal law. The law mandates disclosure of genetically modified organisms (“GMO”) on food labels. The law directs the U.S. Department of Agriculture (“USDA”) to establish, within two years, a nationwide mandatory disclosure standard for bioengineered foods and the labeling procedures. This means that the law itself does not define the standard, but instead gives the USDA significant discretion to define and implement the required disclosure.

Below are some things manufacturers should know about the law:

- Preemption of State Laws. The new law specifically preempts all state and local labeling requirements applicable to genetically engineered (“GE”) foods that do not mirror the language in the law. This would even apply to state laws already passed, including Vermont where mandatory GMO labeling went into effect in July.

- Defining Bioengineered Food. The law defines bioengineered food as food that contains genetic material “that has been modified through in vitro recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) techniques” and “for which the modification could not otherwise be obtained through conventional breeding or found in nature.” This definition could be interpreted as quite restrictive, so it will be important to watch the rule-making process to see how the law is interpreted.

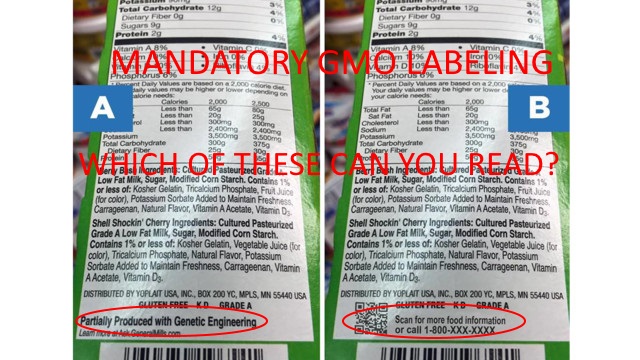

- Labeling Requirements. The law does not specify GMO labeling standards, this is left up to the USDA to determine. However, the law does state the methods to disclose GMOs in food, such as text on the packaging, a USDA-created symbol, or an electronic or digital link (such as a QR code) selected by the manufacturer. Small food manufacturers are provided the additional flexibility to disclose GMO ingredients either by listing a toll free number or link to website containing the disclosure on their labels. The purpose of the law was to disclose GMO ingredients on food labels so consumers searching grocery store aisles could make informed decisions, but law effectively fails to achieve its purpose because “disclosure” can be a link to somewhere else, not on the label itself.

- You Aren’t What You Eat. Meat from animals that consume bioengineered food are exempt from disclosure. Specifically, the law prohibits the USDA from considering any food primarily derived from an animal because “the animal consumed feed produced from, containing, or consisting of a bioengineered substance.” So, for example, you go into a store to buy some beef for a family barbecue and, because of your concern about the safety of GE foods, you want to purchase a GMO free product. You’re aware that most cows slated for consumption are fed a diet containing mostly corn, a majority of which is bioengineered. The label doesn’t disclose GMO ingredients, so you think you’re safe. Think again. Even if the cow eats nothing else but bioengineered corn its entire life, the meat is not considered GE under the new law. Thus, Congress is betting that consumers will be uniformed about the provisions in the law and think their meat is non-GMO, even if its arguably not.