“Whoa, hold on,” you say, “I’m a craft brewer. What does the FDA have to do with me?” Well, that’s a good question. As a brewer you are already familiar with your state liquor agency and the Tobacco, Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), but what you probably don’t realize is that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also regulates your operations. With the increased focus on food safety, and additional regulations under the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), it is only a matter of time until FDA comes knocking on your door.

“Okay, you’ve got my attention,” you respond. “So what part of my business does the FDA regulate?” Glad you asked. The FDA has jurisdiction over many aspects of your business, including both the inputs to and outputs of your operation. Below are just some examples:

Registration:

Just like food manufacturers, breweries are required to register as a food facility with the FDA and renew their registration every two years. This registration requirement applies regardless of whether you brew domestically or overseas (i.e., import beer into U.S.A.).

Labeling Requirements:

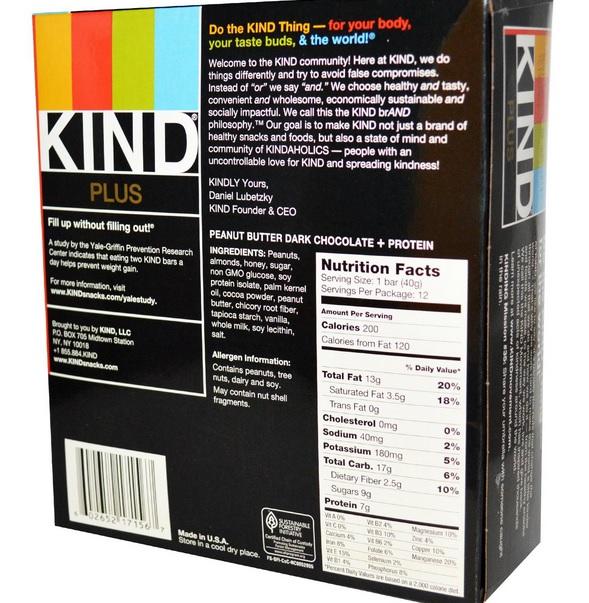

Beer that contains both malted barley and hops are subject to TTB labeling regulations; however, beer that doesn’t contain both malted barley and hops (i.e., rice or wheat beer) are subject to FDA labeling regulations. These regulations require additional disclosures, including: ingredients (such as spices, flavorings, colorings, chemical preservatives); allergens, such as wheat; and nutritional facts (think of that dreaded word “calories”), of course unless it meets certain exemptions.

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs):

Federal regulations have established GMPs for the manufacturing, packing or holding of human food, which includes several of the steps in the beer-making process. Storing and holding grains and other food products for processing and beer for shipment is also subject to regulation. In order to comply with these regulations your operations need to be sanitary, you must perform an analysis of your operations to address any potential hazards, and implement GMPs to minimize such hazards.

Reporting and Record-keeping:

Food safety continues to be a primary concern of FDA and new regulations under FSMA. To ensure your brewery remains compliant you must keep records of the immediate sources of food and the immediate recipients of products you sell. In the event of food safety incident, such as the release of an adulterated product from a production, bottling or manufacturing facility, FDA may require the release be reported. These record will assist brewers and FDA in identifying the sources and recipients of the adulterated products.

Bulk Sales:

Bulk sales of foods and processing byproducts, such as spent grain for animal feed, are subject to FDA regulation. Brewers already implementing human food safety requirements would not need to implement additional preventive controls or GMPs for animal food, except to prevent physical and chemical contamination. This requirement applies even if you’re donating the byproducts for use in animal food.

Food Service and Sales:

In addition to selling beer, do you serve food or sell packaged food products, such as olive oils, cheese, meats or other snacks, in your tasting room or brewpub? Food products served or sold on premise may be subject to federal, as well as state or local, regulations. While exemptions that may apply, you should make sure you stay in compliance with the law.

Inspections:

Under the rules promulgated under FSMA, the FDA is obligated to inspect every brewery in this country over the next several years. This means the FDA can observe your manufacturing processes, inspect your facilities and every aspect of your operation. They also can review your records and take photograph your operations. You should be prepared for any kind of surprise inspection. Also, if the facility fails to meet compliance standards on the first visit to your brewery, FDA will reinspect at a later date and you will be charged at a rate of $221/hour.

As you can see, the FDA has quite a bit of regulatory oversight over your brewery. But it’s not too late to take action to ensure your brewery is compliance, as many of the food safety rules under FSMA have yet to take effect. If your brewery is unsure whether it is in compliance with, or need assistance in adapting your brewery to meet, FDA regulations please contact our attorneys at Morsel Law.

Earlier this year, Hampton Creek Inc., the maker of Just Mayo, was sued by Unilever, the maker of Hellman’s mayonnaise, and accused of false advertising for calling its egg-less spread “mayo”. Even though experts thought the claims were strong, the case was eventually dropped due to the negative publicity Unilever received which painted it as a corporate bully. As mentioned in an earlier

Earlier this year, Hampton Creek Inc., the maker of Just Mayo, was sued by Unilever, the maker of Hellman’s mayonnaise, and accused of false advertising for calling its egg-less spread “mayo”. Even though experts thought the claims were strong, the case was eventually dropped due to the negative publicity Unilever received which painted it as a corporate bully. As mentioned in an earlier